December 2022

In terms of perspective, he seemed to have everything: he was a member of THE YARDBIRDS, a British blues band acclaimed for their sonic experiments that would be deemed legendary, and a successful songwriter whose numbers would be covered by hundreds of artists, including David Bowie and RAINBOW. However, fascinated with sound architecture, as he calls it, from the young age, Paul Samwell-Smith decided to walk away from the spotlight in 1966 to find fame and fortune in the studio, as a producer. Helping bring to fruition classic albums by Cat Stevens – among them “Teaser And The Firecat” – Paul Simon and JETHRO TULL, the veteran can hardly regret such a choice. More so, he doesn’t have time to grumble, as there’s a new Yusuf’s record on the horizon, laid down with Samwell-Smith at the helm; yet Paul found time to talk about his approach and achievements.

– Paul, why do you think people still, after more than fifty years, still talk about you as a bass player with THE YARDBIRDS rather than a producer?

Do they, really? I don’t know. The people who surround me are interested in me and know me, so you’re one of a few people who’s ever said that to me, actually. But I think it’s because of Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page – I think that’s the main reason; and because THE YARDBIRDS remain famous – they are having something of a resurgence of interest, and people are taking them quite seriously now. We just re-released “Roger The Engineer” which is a good album, and I enjoy it – it took me about fifty years to realize that. (Laughs.) We had a lot of fun making it; we felt quite liberated because we’d been under Giorgio Gomelsky’s management, and then Simon Napier-Bell came along, and suddenly we had five days in the studio, which was great. But that’s interesting because in my world everyone I talk to is fascinated, intrigued and gripped by the fact that I was a Yardbird, but the thing I’m most noted for is producing “Tea For The Tillerman” – there’s no doubt about that.

– But when you think about yourself you see yourself as a musician?

No, no, no, no, no, no, no! Definitely, no! I tried to play guitar and was just a dismal failure at it. (Laughs.) Eric Clapton came to see the band I was playing in – it was pre-YARDBIRDS; it was a kind of Memphis blues quartet with Laurie Gain, and Eric was in the audience – and came up to me in the interval and said, “Do me a favor – don’t try and play guitar”: he thought it was dreadful[, and I think he was right. (Laughs.) Then, I picked up the bass, because I was gripped by Ricky Fenton who was a bass player with Cyril Davies – his real name was Ricky Brown but he changed it to Ricky Fenton as in “Fender” and “Gibson” – who was a wonderful, wonderful bass player. He had this habit of going up and starting, (sings and claps) “dee-do-da-doo-dow” – running around high up the bass, and that sounded so good, and I spent a lot of time with THE YARDBIRDS whipping them up into these frenzied high notes on the bass and making everyone go crazy. That’s what I was doing: I was driving the band from the back, with Jim McCarty and making these crescendos and, as some of the songs would last ten or fifteen minutes, we had two or three climaxes in the song. It was fun – I loved it! My bass playing was never musical. People like Jack Bruce had me floored, I didn’t know how, or where, they could do what they did; it was beyond me – it was musically beyond me (laughs). But later, when I became a producer, I realized that I did have a musical thing to say, especially when I could persuade other people to play them. So I’m not really a musician – I’m an architect: I put sounds together and build this construct – a structure out of sound, and that’s where the person lives, being in front of your face, singing the song, and I would put things in the background. An acoustic bass is a wonderful thing to put underneath. It just gives you something to stand on.

– But your playing was just as melodic as it was rhythmical?

Yeah, I suppose – but very 12-bar-blues-rooted. But the minute I was put into things like “For Your Love” – although that’s not a very good example – anything that was melodic, it just was not my thing, that’s not what I do. I listen to jazz bass players and I love them; they’re very clever – they are clever because they know which notes to play, and sometimes it’s a third above the root or a fifth above the root, and it’s wonderful because it puts the whole thing like this. It’s how they think – and I didn’t think that way. But I’d liked what I played – I’m not saying I didn’t like what I played: it was good, it was very exciting. But there’s something about music, which is people who play the notes. You say, “Oh the major diminished seventh there is perfect,” and I’m like, “What?” I could learn that but it’s not how I operate. I listen to it and think, “Uh, the major diminished seventh really makes the things quite sad at that point, and I like that.” So it’s not what it’s called; it’s how to get there is what intrigues me. Being a bit plebeian about it; it’s not quite as simple as that. Yeah, it’s not how I feel about it. I happened to play the bass; apart from BOX OF FROGS, I haven’t played it much since – I don’t pick it up and play, and if there was a band that I could play with they’ll be in shock (laughing) dragging into the 12-bar blues.

– The crescendos you mentioned: weren’t they what you called a “rave up”?

Yes, sort of. That’s what the manager decided to call it, really, but yeah. I called it “a climax” more than anything. It was all guess-making; it didn’t mean to be aggressive.

– Earlier you called yourself an architect. So how the intellectual, cerebral thinking of an architect went along with the rave-up, a purely emotional thing?

It’s not an intellectual architecture; it’s how does it make you feel. With rave-ups, I was emotionally creating a climax, and when I’m asked to put this into shapes – it’s interesting, I haven’t thought about this much – I didn’t really think about shapes with THE YARDBIRDS’ stuff as much as I did with all my Cat Stevens [records] and everything I’ve done since as a producer. The buildings, the space that I’m creating is important, very important, but with THE YARDBIRDS it wasn’t the space – it was the excitement. So I can’t see the difference between the intellectual and the emotional. Ha! You’re making me think.

– Let me quote Jim McCarty. He described you, when you were a kid, as “overflowed with self-confidence and relentlessly curious”…

Self-confidence? Oh, I think it was all the front. (Laughs.) But as for curious, yes, I was very interested in science and engineering, and physics, and I liked that, but I found chemistry a little bit too complicated; CH3OH2 and stuff like that is hard work. But setting light to some gas in a tin which has two holes punched in it, it’s exciting – I loved that. I used to make explosives quite frequently.

– So, given this mindset, do you think you were destined to become a producer?

(Long pause.) I didn’t see it that way, no. I think that I was working my way through and, having played in THE YARDBIRDS for two or three years, I was quite successful, but it wasn’t what I wanted to do. I was never happy standing on-stage in front of a thousand screaming girls; that wasn’t it for me, I wasn’t interested. I was interested in something else, and the minute I could start putting things together, like putting a harpsichord on “For Your Love” – that, for me, was a delight. It was something I loved from when I was a kid, when I listened to [Eartha Kitt’s] “Old Fashioned Millionaire”: I loved the harpsichord on that, and I just adored the sounds in a way it did something to… It sounded like a box of some kind – it’s lovely, I loved it. So the minute I was able to bring that into something that had been created by Graham Gouldman who wrote the song… I’m not really much of a songwriter, either; it’s not what I do. So taking “For Your Love” and putting a harpsichord to it, I don’t know if I was destined for that but it was something that I found that I could and wanted to do. I could express myself with this – it was nice. And when I saw it worked I realized that getting people like Cat Stevens and Carly Simon to sit down in front of you on the guitar and in some cases on the piano and just sing their song to you, which was a very personal, intimate experience, to sing the song you’ve never heard before, that’s amazing. But to be able to take that and put it into context, to maintain its intimacy and immediacy and just decorate it, was just wonderful. I don’t know if it was a calling – I didn’t wake up at the age of five and think, “I’m going to be a producer”!

– But when you did transition into this role, did you feel comfortable from the beginning?

Yeah, sure. I liked it. I did. The breakthrough for me was when Keith [Relf] and Jim of THE YARDBIRDS formed RENAISSANCE: then I was able to… I mean I was working before that on various bits and pieces – I was friends with THE SCAFFOLD, and I worked with them on one of their albums. We also had a session with Jimi Hendrix on guitar and Paul McCartney on drums, stuff like that, which was fun. And I was in touch with lots of very interesting people. Peter Asher was a good friend – we were both interested in record production. But then RENAISSANCE came along, and I realized I could work with this band, which were old friends Jim and Keith, and Keith’s sister Jane. That was a good album – I like that. They were extraordinary with their halfway jazz, especially John Hawken, the pianist, and Louis Cennamo, the bass player, were very good, and to make them sit down and play… Goodness me!

– You said you’re not a songwriter, but there’s at least a couple of songs, which you co-wrote, that have hundreds of cover versions: “Still I’m Sad” and “Shape Of Things”…

Jim and I wrote “Still I’m Sad” at my girlfriend’s house in London one night. She had a nice, big grand piano in the front room, and I sat down and played. It was definitely just based on a sound I’d heard, which was a Gregorian chant, and I liked that “ooh-ooh-ooh” – the way the voices go with almost no words – I loved that, so we sat down and recreated that between us. It was not so much a song as a mood, and then, of course, you have to write words, which is hard work, and I wasn’t very good at that. “See the stars come falling down from the sky / Gently passing, they kiss your tears when you cry”: meh!

– It has a nice phonetic flow, though.

Yes, sure, I’m not worried about that; it’s just as a piece of poetry it’s not very good, is it? Actually, it’s very hard to put poetry to music, it doesn’t work – it’s too intellectual, it’s too complex – it makes the brain go places where music does the links for you, with chord changes and so on – and if the words don’t go with that, you’re fighting as music and words try to do two different things. I’m impressed with Elton John and Bernie Taupin: I think they did some wonderful songs together – that was nice. Bernie’s a great lyricist.

– Do you have a favorite cover version of your songs? They lend themselves to very different arrangements: RAINBOW and BONEY M recorded “Still I’m Sad” and heavier bands, like NAZARETH and RUSH, did “Shape Of Things”…

No, I don’t. No, I can’t… Son, you catch me up with that kind of thing! I’ve not heard any, though; I probably had to but I hadn’t treasure them. So I don’t have a favorite. By the way, “Shapes Of Things” was a very different approach. We were in the studio somewhere in America and we had to write a song, so Keith and Jim and I sat down and did that, you know, we wrote this intro (imitates rhythm) “Diggity-diggity-diggity-diggity dum-dum-dum-dum”: the bass drum is the root of that really, and two chords. Yeah, it was nice, and then we – mostly Keith – threw some lyrics together.

– You mentioned “For Your Love”: I assume it was you who brought it to the band because you produced Graham Gouldman’s group THE MOCKINGBIRDS.

You know, that came as a surprise to me when I was looking at something recently – this happens when you get old and you’ve got a long chequered history (laughs). I’d forgotten that I produced Graham but anyway, this song was brought to us by Ronnie Beck of [music publishers ] Feldman’s because Graham had taken it up to THE BEATLES, and they were delighted but they rarely did other people’s songs. So Ronnie said we should do it – so we did. It wasn’t a close relationship between me and Graham that caused that, and I don’t remember much about those days, you know; THE MOCKINGBIRDS – I don’t remember a thing about those sessions, not a thing! We tend to make up stories that fit the facts (laughs), especially over the years, and you don’t actually remember something – you’re recreating it from basic information you have in your brain. And so we tend to want to write: yeah, wouldn’t it be great if Graham and I had worked together on THE MOCKINGBIRDS, and then Graham said, “Oh, I’ve got a song for you, ‘For Your Love’ – do you want to hear it?” Yeah, that would have been terrific – but no, that didn’t happen. We had a demo brought to us – and I’ve got it with me, by the way.

– So you didn’t discover him as a songwriter?

No, no, no, no, not at all, not at all. Graham was already fairly well-known. He’s a lovely guy; I like him a lot. And he came back on the BOX OF FROGS sessions, when we redid “Heart Full Of Soul” – he came as a guest to Ridge Farm [Studios], where we were playing, and stayed with us. A nice guy.

– When you decided to become, and became, a producer, where did the expertise come from?

I had been recording at home since I was a kid. My brother, who was five years older than me, had some friends, and one of those friends had a tape machine that he brought and lent to me, and I was playing with it. I was recording all kinds of nonsense stuff, like Goons shows, and tried to do my own Goon show bits and pieces, and then, when we started playing guitars, I’d record it on tape. And then I’d heard Les Paul and Mary Ford, and I realized you could multitrack by putting one guitar on top of the other and then recording it from one machine to another and back. I also had a wire recorder, which was a very early, wartime sort of thing where instead of tape you’d use fuse wire wound from one reel to another and to a little, tiny head that put magnetic stuff on it. So I was into all that – that’s what I did as a teenager – and I loved sound effects. I was very into sounds. I got a sound of girls screaming at the concert with all the 78 RPM or something, and I slowed it down to half-speed, so all the (screams at high pitch) “e-e-e-eh” sounded like a horror hospital, like a ward with insane people running around with very little clothes on, their hair flowing behind. (Laughs.) That’s what sound does to me – it takes me elsewhere!

– Back in the day, when you quit THE YARDBIRDS, you said in an interview, “Naturally, there are things I regret about leaving – like the money.”

Oh, did I say that? Maybe just after the band. I think I went through the period of not having any, and there was THE YARDBIRDS off touring America and stuff, with money that never be. (Laughs.) When we actually folded THE YARDBIRDS, the company owed the bank three hundred pounds or something like this, and the bank did its very best to get it back off on us. No, there was not a lot of money involved with THE YARDBIRDS, so why I said that I’m not sure. It was a good answer to someone asking.

– By the way, you played on Paul Jones’ version of BEE GEES’ “And The Sun Will Shine” with McCartney on drums and Jeff Beck. Was it after you left the band?

Yes. As I mentioned, Peter Asher was a friend, and he was the producer of that track. We went to Abbey Road, I think – EMI, anyway – and I had a good bass line which I thought of and which I liked, but it was a line that should have been played by cellos as opposed to just bass. (Laughs.)

– But why didn’t McCartney play bass?

Well, Peter was the brother of McCartney’s girlfriend [Jane Asher] and they were quite close – not just because of that, but because Peter was in the pop business. THE YARDBIRDS bumped into PETER AND GORDON several times in California, actually.

– Since we’re talking about McCartney. You produced a session for McGOUGH & McGEAR, the McGear being Paul’s brother Mike. Was it also through Asher?

I can’t remember why I knew McGear, but he was a pal. I think I met him at “The Marquee” and Roger McGough through John Gorman – Roger was a good friend too, back in the Sixties; we strolled through the streets of Soho at eleven o’clock at night, talking about this, that, and the other, and that was fun. I liked them – they were nice, and then they [as THE SCAFFOLD] had “Lily The Pink” and stuff like that. So it wasn’t through Peter; it was through me being in the band and us meeting each other. And when I left THE YARDBIRDS, we stayed in touch – we were even closer in touch.

– What was your first full-blown work as a producer when you felt that you really nailed it?

I think my first real go was, as I mentioned, with RENAISSANCE. Keith and Jim approached me – they’d carried on after I’d left THE YARDBIRDS – and said they broke apart and formed a new band. They liked my production skills and asked me if I would like to produce them. I phoned Jac Holzman in America and asked, “Can I make a record with them?” He said, “Sure!” I can’t remember what he said now – probably 3,000 dollars, or something like that. He probably said that his office in London would help us and would pay for the studio. So we did: we went into Olympic Sound, in Barnes, where I worked with Andy Johns as an engineer and Keith Grant – but Keith was not really engineering for us; he was at the Record Plant studio at the time. Yeah, that was my first proper full album, the first one I’d really made. And that was different, that was nice – I enjoyed that.

– Did you also enjoy working with ILLUSION later on?

Yes, I did, but that was a bit of a continuation of [RENAISSANCE]; it wasn’t as exciting. We’d already worked together quite a lot, and this is what happens.

– You sang backing vocals with them too?

Well, I’ve spent my life doing backing vocals – I love them, I just adore them; that’s one of my passions, and that is where I get musical, I suppose. (Laughs.) I did them on, for instance, one of the earliest great ones was… well, well!.. “Tea For The Tillerman”

– Was that the “banshee voice” that you’re credited with on a Martin Stephenson record?

(Laughs.) Was that me? I don’t remember. Probably, but I like the idea of banshee voice – it’s good.

– Do you remember the first time you met – or heard – Cat Stevens? What was your impression of him?

I first heard Cat on the radio singing “I Love My Dog” and “Matthew And Son” and thought he was a young singer-songwriter with quite heavy orchestration behind him that made him a Sixties pop star. But it was good stuff and came at you from a different perspective from the usual fare. And there was something maybe Dickensian about him. Then, after I had produced an album of RENAISSANCE for Holzman, Jac recommended that I take it to Chris Blackwell in the UK to find a release for it. Chris liked and signed it, and a few weeks later asked me to meet with a new young artist he had signed, called Cat Stevens. I went to Steve’s parents house-restaurant in Tottenham Court Road and there was introduced to him and maybe 10 or 20 songs that he had been working on during his TB illness. Those were the songs that went to make up the bulk of the first two albums we made.

– Whose idea it was, yours or Cat’s, to move on from his Sixties pop to a singer-songwriter, acoustic-based style? Who did devise the sparse sound on “Mona Bone Jakon” and further on?

It wasn’t a conscious decision on either of our parts. He sat and played guitar – mostly – or piano, and it seemed obvious that we should go into the studio and lay down some tracks with just that intimate magic he had. But right from the start I wanted a second guitar player to help lay down the tracks, to give color and rhythm to the basic song. My initial instinct was to ask Jon Mark to come and play for me, as he had already come to the studio to work with Jim McCarty and Keith Relf on some earlier recordings we had made, called “Together Now.” He was brilliant but said he couldn’t do the sessions as he had prior commitments playing live, so he recommended a friend of his called Alun Davies. And Alun is still working with Yusuf some 53 years later. He was absolutely perfect to compliment Yusuf’s playing. Sometimes you get lucky.

So we tended to go into the studio and lay down a basic track of just guitar, or guitars, and vocal, and later we would overdub acoustic bass played by Jim Ryan, and sometimes drums by Harvey Burns, and often piano or synthesizer keyboards that were always played by Yusuf himself, and backing vocals, which Yusuf, Alun and I did between us. I found that it wasn’t necessary to add too much to the basic tracks as they seemed to hold all the magic when they were kept simple. Yusuf was such a charmer, being able to sit and enthrall by just playing and singing, but he also had a wonderful ability to direct drums and percussion on our recordings, often telling Harvey exactly what to play, which Harvey did with great talent. The final “topping” on some of the tracks was Del Newman’s string arranging. He was recommended to me by another of Jac Holzman’s associates called Carol Peters, who worked for Elektra in the UK – we had met while working on the aforementioned RENAISSANCE album. I had spent so much of my life worshipping Dylan, Joni Mitchell and Paul Simon that I was only too happy to bring some of that simplicity into my studio.

– Was it you who brought in Peter Gabriel and Rick Wakeman to play on, respectively, “Katmandu” and “Morning Has Broken”?

You know, I really can’t remember whose idea it was to use Gabriel, but it doesn’t really matter; Yusuf, Alun and I were sort of “in it together” and you got who you could. Peter was lovely, very quiet and I think very intimidated. But Wakeman was definitely Yusuf’s idea. We were working at Morgan Studios in Willesden – and this was probably 15 months after we had started recording “Mona Bone” – and Rick was working in another of their studios down the road, and Yusuf bumped into him and asked if he would like to come and play piano for us. They both spent a long time working on that piano part to refine it, with Yusuf suggesting things and Rick adapting them. I have often been asked how did I get such a clear and dynamic piano sound for that track, what microphones, what piano, and my answer has always been “Rick Wakeman’s fingers”!

– How did Cat’s attitude change with his conversion to Islam?

He was always looking for something. His brush with TB had been a profound experience for him, and had made him much more introspective, which shows in his work I think. Then when he had some success and had to deal with all the commitments and demands that fame and touring brought with them, he was searching for answers: there were numerology and eastern religions – reflected in “Numbers,” “Catch Bull At Four,” and “Buddha And The Chocolate Box,” for example – so his work became more complicated. Instead of wandering into a studio at 10 pm to work all night with me on some basic songs, he was now touring the world with an entourage and a full band, so he became a sort of band leader with a “machine” behind him, and he brought some of this organized energy into the studio with him. So instead of starting from a very simple voice and guitar or voice and piano perspective and building on that, we were often laying down more complicated basic tracks. It was a different approach. He was living a complicated and demanding life as a global entertainer and I think religion came as a salvation and calming influence, giving him a new direction and purpose.

– What have you learned from Yusuf after working with him for many years?

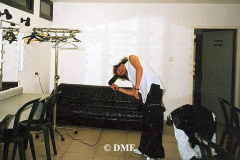

With Yusuf and Maartin Allcock on a coffee break in Brussels where they recorded “The Laughing Apple” in 2014-15

With Yusuf and Maartin Allcock on a coffee break in Brussels where they recorded “The Laughing Apple” in 2014-15I suppose what I have learned most of all is that it is best to capture an artist like Yusuf while he is in the basic and simple stage of creating. I have found that the artist themselves don’t really know what magic they have at their fingertips if they simply do their thing and sing and play. The more you allow them to embellish and plan ahead with a production the further away you may get from the basic charm and magic that they – unknowingly – possess.

– What would you say you brought to his records?

Simplicity and directness.

– How did Yusuf explain the point of rerecording “Tea For The Tillerman” anew, and what were your contributions to the project as a producer who expanded his techniques in the decades that passed since the original album was out?

I think the best anecdote about “Tillerman 2” is that we recorded a new 2019 version of “Father and Son” and brought in a version from Yusuf live at the L.A. “Troubadour” in the early Seventies singing the part of the Son, so we had Yusuf aged seventy-something singing the Father and Yusuf aged twenty-something singing the part of the Son. It’s beautiful, and it was that concept that we discussed before going in to the studio that seemed to encapsulate what we were doing. How did these songs sound today, with age and so much water under the bridge? As for expanded techniques, I don’t know – I just stumble around and try to help…

– One of the new people on “Tea 2” was Peter-John Vettese. You know him from working with JETHRO TULL?

Yes, I met Peter Vettese when I went down to Chelsea where Ian Anderson had his studio and was recording “The Broadsword And The Beast” – it was Gerry Conway who was playing drums for Ian and who suggested I come down to help with the production. Peter was a revelation – a very intelligent and talented live-wire who could also just rock when needed: it’s quite a combination. And we still work together quite a lot some forty years later. And Peter is still rocking – he’s currently doing a world tour with Zucchero to huge stadium crowds.

– “The Broadsword And The Beast” saw TULL transition from folk-rock you might have been familiar with to synthesizers-driven style. How instrumental were you in implementing such a change?

This is strange for me – I wasn’t aware of any transition from or to anything. I just did what I always did – I looked at and listened to the music that was presented to me in the studio and did my best to get it recorded in a faithful and representative manor. That sounds pompous, but it was always a lot harder to do because, as I’ve said before, recording is a process of deception, or sleight-of-hand/ear, to make the listener think they are hearing the true sounds without realizing they are being slightly deceived. One of my great criticisms of today’s music is that it is very clearly a total deception, with compression, complicated reverbs and auto-tuning completely obscuring the humanity, fragility and flawed nature of a great natural performance.

– Yes, when you started out, it was all analog recordings and it’s digital now. What sound do you personally prefer?

That’s a complicated question – I think I like both systems, analog and digital. Digital is so much more flexible and adaptable, but this also means the sounds can be doctored, changed, massaged, and even tortured with so many digital processors. Analog tended to always need rather gentle processing with classic compressors, EQ and EMT reverb plates so, of course, it doesn’t sound as if it’s been hung, drawn and quartered like a lot of digital does.

– Another transitional, from prog to pop, album was Chris De Burgh’s “At The End Of A Perfect Day.” What was special in this record for you to even provide backing vocals for it?

Again, “transitional”? I got a call from Jerry Moss at A&M asking me to maybe produce Chris De Burgh for him. Chris was a lovely Irish storyteller who could enchant by simply singing with his guitar, and I just went in the studio with him with my usual troupe of great and eccentric musicians and we did what we could. And I sing vocals on as many of my records as I can – I love that process of adding human voices to a track. Just listen to “Perfect Day.”

– The “usual troupe” that you’ve just mentioned: how important for you was using the folk rock elite on many albums you worked on?

The “folk-rock elite” were really just good friends that I had had the good fortune to bump into – and drink with! – over the years, thanks to Jon Mark and Alun Davies initially, and then Simon Nicol, Dave Mattacks and Dave Pegg. I think I rather took them for granted, but they were a gift.

– You also played quite a few instruments yourself on ALL ABOUT EVE’s self-titled album. What made you want to add to it in such a way?

Again, I found myself in the studio with ALL ABOUT EVE, and we just did what was necessary to try to capture what was there. You all end up in it together, at a residential studio like “Ridge Farm” or [Richard] Branson’s “The Manor,” and it’s like being cast adrift on a desert island, or perhaps being locked up in prison, and you just work together to realize the material with whatever may be on hand: emulator strings or sound effects, backing vocals, percussion – bashing dustbins or chinking finger cymbals – whatever comes to mind or hand.

– EVE’s “Scarlet and Other Stories” saw Julianne Regan and Tim Bricheno break up their partnership. How often did you as a producer have to deal with personal relationships as opposed to purely creative ones?

I was only slightly aware of tensions between Julianne and Tim, and they certainly didn’t bring much of that into the studio. They were always very professional and I was fond of them both. Have a listen to Julianne’s performance on “She Moves Through the Fair” which we put together at “The Manor” in Oxfordshire. I loved making that track, and the special atmosphere that we all created on those sessions can be heard there. I suppose I tend to “fall in love” with any artist I am working with, so any personal problems become part of the overall process of coaxing an album out of the soup. The more soup the better.

– You worked with many different artists. Do you have a preferred genre or style?

Yes. My forte has always been singer-songwriters: taking the person, the singer, and the song, putting them here, dead center, and putting behind them whatever – it might just be one guitar or it might be a 61-piece orchestra as we did with Yusuf about two years ago. I’m happy doing that; it’s a question of… I need the artist as a focus, and I’m not the kind of producer who writes and produces a hit song around somebody who comes and sings. I have to have the person there, in front of me, performing for me and to me, and then I can build around them.

– I’d say it’s very often folk-based for you. Do you like traditional music?

Yeah, yeah, sure. I grew up loving it. Joan Baez – and Bob Dylan, of course – was completely my world then.

– What about you producing AMAZING BLONDEL?

Oh yes, that was fun! Chris Blackwell said, “Hey, what if you tried this?” So I did. They were signed to Island, and they were lovely guys, very nice. I tried to mess around a little bit, and we got Jim Capaldi of TRAFFIC to come and play drums on one of their records, but they were basic and quite rigid, and… I have to be careful as to what I’m saying, because it sounds rude, and I don’t mean to be rude at all but they weren’t… You couldn’t take them and put an orchestra or a zither behind them (laughs) – they were a bit locked into what they were: acoustic, medieval acoustic, with lutes and so on, so we had fun with that. We made nice albums, gentle, I enjoyed them.

– Did you also work with John Martyn?

No. I wish I had. I would have worked well with him.

– And Jimmy Cliff’s “Synthetic World”: this I guess is your strangest credit, genre-wise?

I think that was Chris Blackwell again. I was at Island, and for some reason he wanted me to do that. They had this artist who needed a hit, and they thought that I could do that – and, of course, I couldn’t. (Laughs.) But it was a good track. And then Cat Stevens took him and did “Wild World” with him, didn’t he, which was released before our version of this song – as a single, in the UK. It didn’t worry me, but I can tell you our version of “Wild World” is too pretty damn good, it’s still being played. (Laughs.)

– It looks like you had a special connection with female vocals, having worked with Jane Relf, as you have mentioned, Carly Simon, Claire Hamill, Beverley Craven…

And ALL ABOUT EVE as well – that’s a good example. But it’s the same thing as with male voices, there’s no difference for me. As long as the person can sing and play for me, then I can work with them. Except, of course, that you tend to fall in love with your female artists, which is always a bit dangerous, but it’s necessary – you have to, I’m sure; film directors have the same thing. If you’re working with someone intimately for two or three months, you form a bond with them: it’s inevitable and it’s good. I wasn’t falling in love with my male artists (laughs) – I was only in love with the music that they made.

– How come you played and sang on Kate and Anna McGarrigle’s “Love Over and Over” that you didn’t produce?

I was asked to produce Kate and Anna by a friend, Charles Levison of Arista Records, and I went to Canada for a few weeks to work with them at “Le Studio” near Montreal. I took Alun Davies with me, and the girls were lovely, so we had a good time, but the sessions didn’t really work. I think everyone thought I could give them some commercial success but it doesn’t work like that, certainly not with me. That’s where that track would have originated, and I guess I did backing vocals on it, which they then used at a later session and mix.

– You’re also credited with PUSSYCAT DOLLS’ “When I Grow Up” but that’s because they used THE YARDBIRDS’ sample, correct?

They picked up on that all by themselves and wrote to their publishers at EMI and Sony, asking if they could use that riff. Sony said yes, which was good actually, and, lo and behold, we got millions or billions sales of that song. Incredible! Cor blimey!

– It wasn’t a single stretch with Carly Simon: you started working with her in the Seventies and continued into the Nineties.

It wasn’t a continuation. We stopped working together. I remember that, for one reason or another, I stopped working with her after “Anticipation” and then we got back together in the Eighties in New York: she contacted me and said, “Would you like to work?” I said, “Yeah!”, and I went out there; and we did “My New Boyfriend” which was great. I worked on the backing track in my shed, and then I went to New York and did the whole thing again. Another track of hers which I worked on was “Do The Walls Come Down” which actually I composed in my shed and then she wrote lyrics to it and sang on top of it.

– It was your first writing credit in years. What made you start composing again?

I was writing in my shed but once I got my own recorders and keyboards, I was able to mess around in my own time. And I wrote decent pieces, you know. “Do The Walls Come Down” was a good example, a good piece of music, but I can’t write lyrics like that – they’re just too clever. The stuff in my shed shows that I’m not a very good singer nor a very good songwriter. That’s not something I do very well, but they’re okay – some of them.

– Was Carly your first American artist?

Yeah. It was Jac Holzman, you see. I’d produced RENAISSANCE for him and then I’d been to New York and worked with Jac, and I had started doing my mastering at Sterling Sound which Jac recommended – I’ve used it ever since. When Carly came up, she had already had one hit record, so Jac phoned me and said, “Would you produce her?” So she came to England.

– Why did he ask you, not an American producer?

He liked my producing. He thought that was unusual. Of course, Jac would have heard [Cat Stevens’] “Mona Bone Jakon” at this point, I’m sure. In fact, I went to New York after working with Chris Blackwell on that album in 1969-1970 – I went there with the [record’s] master and I played it to CBS who listened to a half of one track and said, “No, that’s not for us, thanks a lot.” So I went to Elektra, because Jac was a friend but he wasn’t there, and I didn’t play it for him, and he missed out on that. Then I went to see a friend of mine, whom I’d met, Carol Peters and her husband Larry, and I stayed with them in California, and Larry took “Mona Bone Jakon” to A&M to see if they were interested. They said yes, so I got the deal. It’s a nice story. So Jac would have heard “Mona Bone Jakon” and possibly “Tea For The Tillerman” and recommended that I work with Carly.

– Most of the artists you worked with are British. So how did your involvement in Paul Simon’s “American Tune” come about?

I think Paul Simon had heard of my work with Cat Stevens and Carly Simon, and he wanted to come to the UK to try recording a song with me to see if it worked. We recorded at Morgan Studios in Willesden, and I had Alun Davies and Jean Roussel, Yusuf’s keyboard player, on stand-by in the studio to do the backing track, and Del Newman had done a string arrangement, which we put on the next day. Roussel was not used because Simon was determined not to use a piano on the session, because “Bridge Over Troubled Water” featured the piano so heavily he wanted to avoid similarities. I never thought “American Tune” worked as a production – I think I missed getting a personal and intimate performance from Simon that we could have built around, which is how I usually worked. The strings are lovely, though.

– You left your stamp, together with Alun Davies, on Murray Head’s “Say It Ain’t So” and “Voices” – and you both were absent from “Between Us” that was recorded between these two albums. Why?

I produced the “Say It Ain’t So” album at Morgan Studios, Willesden, and Alun Davies was indeed a crucial mainstay of those sessions, as he and Murray worked together so well. Many of the tracks were originally just guitars and vocal, and we overdubbed all the rest. Bruce Lynch played amazing acoustic bass on “Say It Ain’t So,” which was also a crucial element it that song, and again an overdub. Then Murray and I became busy and otherwise occupied, so Murray had to go off and produce “Between Us” by himself. We got back together for only some of the “Voices” tracks, as we had drifted slightly apart at this stage.

– There again was the crème de la crème of folk-rock players on those records. Was it difficult to rein them all in and create a unified sound?

No, it was easy, with, as you say, crème de la crème available to come and perform their magic at the drop of a telephone call, and by their very nature these musicians are very sensitive and adaptable to what’s going on around them, so making them sound like they belonged was easy because they did.

– Did you ever want, when working with Cat, to take up the bass and play?

No, not really. I was never that comfortable playing the instrument. And when I started working on production I came across bass players who were so bloody talented it didn’t occur to me to try to do what they were doing. John Ryan initially with Yusuf, and before that Louis Cennamo in the RENAISSANCE band, then Bruce Lynch – just listen to the acoustic bass in “Say It Ain’t So.” And so many more. What I did was fun and quite different in THE YARDBIRDS – driving the rave-up sections with frantic and high-energy lunacy. It just wouldn’t have worked in the intense and focused productions with Yusuf and others.

– What did entice you to return to playing with BOX OF FROGS?

It was Jim McCarty who tempted me back into that project. It was fun to be working with old friends again, and we used “Ridge Farm” studios which were also a lot of fun, with some good food, some good nights in the pub, and some wonderful guests in to sing and play with us.

– Given that “Shed Music” is not a solo album per se, will you ever think of delivering one?

I think the less said about “Shed Music” the better. For a while I thought I had something to say but I pretty soon realized that I was better off working with true talent and not trying to squeeze out what little there was to be found when I worked on my own.